The Legacy of Awadhi Patronage

The cultural legacy of Awadh, particularly under the patronage of its feudal lords, Nawabs, represents one of the most remarkable chapters in the artistic and intellectual history of South Asia. From the early 18th century until the annexation of the kingdom by the British in 1856, the Nawabs of Awadh transformed Lucknow into a thriving epicenter of creativity, where literature, music, dance, textiles, and architecture flourished in an environment of cultivated refinement. Rooted in a complex blend of Mughal, Persian, and regional influences, Awadh’s golden age of artistic patronage left an indelible mark that continues to resonate through contemporary India’s cultural landscape.

Awadh's ascendancy as a cultural powerhouse came at a time when the Mughal Empire was in decline, and the political vacuum left by the weakening imperial center was deftly filled by the Nawabs. As rulers of this region, which included parts of modern-day Uttar Pradesh, the Nawabs reimagined the role of the court, not merely as a seat of power but as a sanctuary for the finest artistic expressions. From 1722, when Saadat Ali Khan became the first Nawab of Awadh, through the reigns of his successors, including the renowned Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula, the region witnessed an unparalleled patronage of the arts, from architecture to textiles to music.

One of the defining features of Awadhi patronage was its focus on zardozi—a gilded embroidery art that became synonymous with the city of Lucknow. Under the Nawabs, this craft was elevated to extraordinary heights, with exquisite gold and silver threads used to create elaborate motifs on luxurious fabrics such as velvet, satin, and silk. While zardozi was practiced elsewhere in India, Lucknow’s version was particularly esteemed, known for its unparalleled finesse and opulence. The Nawabs, with their keen eye for artistry, made zardozi a central feature of their courtly attire, adorning garments, footwear, ceremonial objects, and even tents with this intricate needlework. As the historian C.W. Gywanne noted, by the 19th century, Lucknow had become the preeminent center for this craft, with its zardozi artisans, known as zardoz, producing pieces that were unmatched in their craftsmanship.

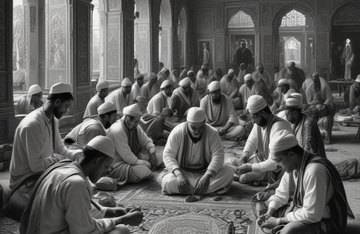

Apart from their renowned patronage of textiles, the Nawabs of Awadh were equally instrumental in nurturing other forms of artistic expression, including music, poetry, and dance. Their court became a vibrant cultural hub where the classical music of ghazals and thumris flourished, further embedding these forms into the region’s cultural fabric. The courtyards of Lucknow echoed with the melodies of masterful musicians and the rhythmic movements of Kathak dancers, both of which were celebrated and refined under the Nawabi patronage. This cultural efflorescence extended to the literary arts, particularly in Urdu poetry, which found a fertile ground in the Awadhi court. Poets like Mirza Ghalib and Siraj-ud-Din Ali Khan Arzu, inspired by the court’s elegance, shaped the poetic landscape of the time, solidifying Awadh’s reputation as a literary epicenter.

The Nawabs’ influence, however, was not limited to the performing and literary arts alone. They also left a profound mark on the architectural landscape of the region, with monumental structures that continue to define Lucknow’s skyline. Building projects such as the Bara Imambara and the Chota Imambara stand as enduring symbols of Awadhi grandeur, blending Mughal and regional styles with remarkable precision. These architectural marvels, characterized by their intricate design and imposing scale, reflect not only the Nawabs' aesthetic sensibilities but also their broader vision for a culturally enriched state. Their dedication to the arts is enshrined in these buildings, which remain lasting tributes to a period of unparalleled creativity and cultural patronage.

While the fall of the Nawabi court following the British annexation of Awadh in 1856 marked the end of an era of royal patronage, the artistic traditions fostered by the Nawabs continued to thrive. With the decline of the formal courtly system, many of the skilled artisans, or karkhandars, who had once worked under royal auspices, transitioned into independent production. Areas like Chauk and Hussainabad in Lucknow became focal points for the continuation of zardozi and chikankari embroidery, both of which had become synonymous with the region’s cultural identity. As these crafts found new patronage among the broader population, they gradually became integral to the fabric of India’s textile heritage, ensuring the Nawabs’ artistic legacy remained alive long after the dissolution of their court.

Today, the legacy of Awadhi patronage endures in the bustling streets of Lucknow, where artisans still practice the fine arts of chikankari and zardozi, as well as in the musical traditions that continue to echo the city’s glorious past. The Nawabs of Awadh left behind not only a rich cultural inheritance but also an enduring spirit of artistic excellence and refinement. Their contributions to the world of literature, music, dance, and craftsmanship continue to resonate, ensuring that the legacy of Awadhi patronage remains a vibrant part of India’s cultural fabric.